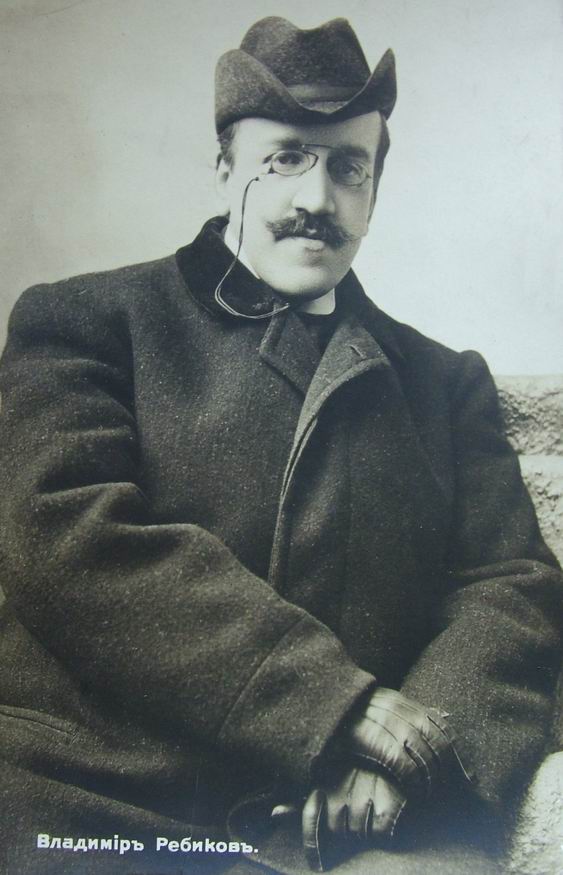

Rebikov, Vladimir 1866 - 1920

Author: Yamamoto, Akihisa

Last updated:April 12, 2020

Author: Yamamoto, Akihisa

Overview

Vladimir Ivanovich Rebikov was a composer who, broadly speaking within the framework of Russian composers, belonged to a generation slightly older than Taneyev and Arensky, contemporary with Glazunov and Kalinnikov, and slightly younger than Scriabin and Rachmaninoff. Surrounded by such eminent masters of symphonism and pianism, he occupies a unique position in Russian music history. During his lifetime, he was variously accepted and evaluated by the musical establishment as a “strange composer” (Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov), a “Russian Impressionist” (Karatïgin), a “blossom of Russian modernism” (Asafyev), an “Expressionist” (Engel), an “interesting, talented, and sensitive painter” (Kashkin), and a “fierce radical” (Kochetov). However, after his death in 1920, his music was incompatible with the official Soviet line, leading historians to dismiss him as a “decadent composer,” one who “lacked original musical talent,” who “confined himself to a narrow world of personal aesthetic experience,” and a “mediocre imitator.” This period of neglect continued, with his large-scale works even being banned from performance. Nevertheless, in recent years, his unique presence in the early 20th-century Russian music scene and the distinctive, mysterious brilliance of his compositions have attracted attention, and understanding of his works is gradually progressing.

Life

Rebikov was born in 1866 in Krasnoyarsk, a large city in central Siberia. His mother was a pianist, and he became well-acquainted with music. While graduating from the Faculty of Literature at Moscow University, he also received private music lessons from Tchaikovsky's pupil, Klenovsky. His love for music never faded, and he traveled to Berlin and Vienna, where he continued his studies under several teachers and encountered new musical trends not yet known in Russia. After returning to Russia, he began serious compositional activity from 1893, while teaching at music schools in Moscow, Kyiv, Odesa, and Chișinău.

His early works from the first half of the 1890s, as he himself later described, showed similarities to “Tchaikovsky's imitation.” This is indeed evident in his early salon-style piano miniatures and dance pieces. Rebikov later stated that to break free from the influence of his great predecessor, he “made an effort not to listen to operas, not to attend concerts, and not to listen to any other music at all.” While it is interesting how much this peculiar behavior contributed to his own creation, instead of engaging with others' music, he reportedly immersed himself in the study of other arts such as painting, architecture, literature, and drama. In fact, his interaction with contemporary Russian art, which gradually blossomed from the 1890s to the 1900s, seems to have had a significant impact on his inner creative philosophy. Furthermore, articles about Rebikov were published in Russian Symbolist magazines such as Vesy (The Scales) and Apollon, indicating that these interactions were outwardly beneficial as well.

とりわけレビコフが自覚的に切り開き、今日でも世紀末ロシア音楽に彼が残した興味深い足跡として認められているのは、和声面・旋法面での独自性である。この側面は、1897年に作曲された作品13の小品集10 Poetic Sketchesで最初に花開いた。このツィクルスは、いわく「いろいろな気分の素描」で、一曲ごとにそれぞれの音響的個性を持ち合わせている。たとえば第2番〈カフカスにて〉では徹頭徹尾解決しない不協和音が連ねられ、終曲〈疑惑〉ではゼクエンツ的に様々な和音が宙ぶらりんのまま連鎖していく。詩人Semyon Nadson(1852-1887)の詩がエピグラフとして添えられていることも、当時のRebikovの音楽以外への関心を物語っている。その後に作曲されたMelomimics, Op. 17 No. 2, “Idyll”ではほとんど全編で全音音階による旋律・和声を採用するなど、Rebikovは新しい音響へと傾倒し、自らの技法を深化させていった。晩年の1913年に作曲されたIdyll, Op. 50では、Satieが行ったように楽曲から小節線を全面的に排除するとともに、手のひらを用いたクラスター的奏法すら採用している。Rebikov自身によると、このような和声・旋法上の新しい実践は「音楽により『気分』や『感覚』といったものを伝え、聴き手を同じような気分や感覚にすること」を目的としていたという。したがって、このようなある種革新的な音楽語法が用いられている楽曲は、その内容と標題が彼にとって感覚的に完全に合致していたということになろう。

This new approach to sound made Rebikov's name known in the musical circles of Moscow and St. Petersburg. He was criticized by composers for the lack of beautiful, melodic lines in his works, for his monotonous rhythms, and for his inability to write large-scale compositions. Furthermore, Rebikov's pursuit of harmonic novelty was often misunderstood as “decadent” or indicative of a “lack of knowledge of musical laws and forms.” However, on the other hand, Rebikov's piano pieces and songs were also featured in “Evenings of Contemporary Music” concerts held in Moscow to promote modern music. His harmonic originality was praised under the name of “atonality,” and critics began to mention him as one of the influential young composers, often discussed in comparison with Scriabin. Many of his works were published by Jurgenson, a company with its headquarters in Moscow and a branch in Leipzig, which actively assisted in the dissemination of Rebikov's works both within and outside Russia. This clear division between misunderstanding and support was typical of the reception of modernist composers in Russia at the time.

In 1910, he moved to Yalta, where he died in 1920. Although his pace of composition slowed after leaving the musical life of the capital, he maintained the ambition to complete large-scale dramatic works such as Arachne (1915) and A Nest of Nobles (1916). He continued to attract attention, for example, with the performance of his dramatic work The Christmas Tree by a Moscow theater in 1913, commemorating his 25th year of creative activity.

Works

Dramatic works, piano works, and vocal works constituted a significant proportion of Rebikov's output. For piano and vocal works, he primarily composed miniatures with programmatic titles. As mentioned earlier, these works feature characteristics such as unresolved dissonances and whole-tone scales, and their titles and musical content are closely linked by keywords like “mood” and “sensation.” “Supplication,” “Belief,” “Regret,” “Loneliness” (from In the Twilight, Op. 23), “Evening on the Steppe,” “A Girl Rocking a Doll,” “Forest Witch” (from Silhouettes, Op. 31) — by paying attention to the evocative titles Rebikov gave, one can gain a deeper understanding of his music.

Since many of Rebikov's works are small-scale and salon-style, they might seem approachable for performers. However, to fully bring out their charm and translate them into sound, performers need the persuasive power to interpret and digest the elements fixed in the score by Rebikov—such as titles, epigraphs, and performance instructions—by connecting them with the keyword “a certain mood,” and then convey that understanding to the audience. Rebikov's works are often compared to those of French Impressionist composers, but compared to Debussy or Ravel, the thinness and simplicity of his textures and the scarcity of virtuoso elements are evident. Nevertheless, this very “blank space” seems to provide the performer with a canvas that fully enables a musical interpretation aligned with the “mood” the composer sought to convey to people (performers and listeners).

One aspect that must not be overlooked when discussing Rebikov's creative output is his dramatic works. He regularly composed dramatic music from the 1890s onwards. Just to list those with opus numbers: Into the Storm, Op. 5 (1893), The Christmas Tree, Op. 21 (1900), Thea, Op. 34 (1904), The Abyss, Op. 40 (1907), The Woman with the Dagger, Op. 41 (1910), Alpha and Omega, Op. 42 (1911), Narcissus, Op. 45 (1912), Arachne, Op. 49 (1915), and A Nest of Nobles, Op. 55 (1916). These are often called “operas,” but the composer himself referred to them as “musical psychodramas” and considered them works structured in a way different from traditional opera. Indeed, examining individual pieces, it becomes clear why Rebikov did not wish to categorize these works under the traditional “opera” genre. Unfortunately, most of these works rarely receive performance opportunities today. Among them, however, The Christmas Tree, also titled “musical psychodrama,” was frequently performed both within and outside Russia at the time and remains Rebikov's best-known dramatic work. It is an unusual one-act play set in “the place and time of its performance” (meaning it could, for example, be set in 21st-century Tokyo), with mime occupying many scenes and only brief sections of singing. Furthermore, while innovative writing similar to that found in his piano works is partially present, it is consciously restrained, making the work generally accessible to the audiences of his time. Also, the waltz from the second scene, consisting of a whole-tone scale introduction and a melancholic F-sharp minor main section, is still often performed independently as a piano arrangement today.

The reason Rebikov's dramatic works are rarely performed anymore can be attributed to the historical context. During the Soviet era, his large-scale dramatic works came to be regarded as “decadent” and incompatible with the official government line, and by the late 1920s, they were formally banned from performance. Although smaller works continued to be published, the loss of performance opportunities for these large-scale works and the government's labeling of them as “decadent” contributed to Rebikov's decline in public attention and scholarly/critical evaluation within the Soviet Union.

Author : Higuchi, Ai

Last Updated: October 1, 2007

[Open]

Author : Higuchi, Ai

Born in Krasnoyarsk, Siberia, in 1866, he was a composer of late Russian Romantic music. He studied under Klenovsky at the Moscow Conservatory. From 1901, he was active as a pianist both domestically and internationally. His early style was influenced by Tchaikovsky, and he composed many warm, lyrical, and elegant works. However, from around 1900, he began to explore Impressionism, for example, by employing the whole-tone scale. A representative work from this period is "Musical Satire" for voice and piano, a small-scale piece in an Expressionistic style. Many of his piano compositions are works for children or small salon pieces.

Works(56)

Piano Solo

pieces (19)

suite (3)

other dances (2)

character pieces (2)

Various works (22)

Piano Ensemble